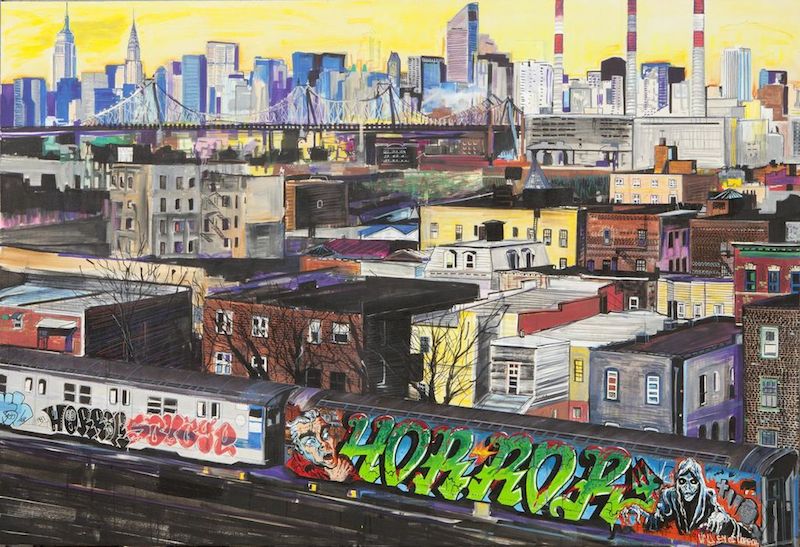

The Valley of Horror (2012) by James Jessop. Photo by James Jessop.

British graffiti artist James Jessop got involved with graffiti in a fairly typical way for a Brit, and it was communication and miscommunication between New York and England that defined his early career and continue to influence him today. Jessop was a young boy of age 11 when he first got involved with graffiti. Today, about 30 years later, he is like a walking encyclopedia of graffiti knowledge, but access to information about graffiti was once not so simple as it is today.

Jessop grew up in a small town outside of London where, at the height of graffiti’s popularity, there were still only about 10 active writers in the entire town. Jessop was into breakdancing, which at the time was also associated with rap and graffiti. After he’d been breaking for a little while, a friend of his told him about graffiti, but Jessop’s friend didn’t really know what he was talking about. The boys began writing graffiti, but they didn’t know to write names. Instead, they wrote phrases like “hip-hop” or “breaking.” Jessop began his graffiti career by attempting to imitate graffiti, but he was pretty much doing it dead wrong and had no idea, because he’d actually seen almost no graffiti. He based his work on what little information he had, and did the best he could with that.

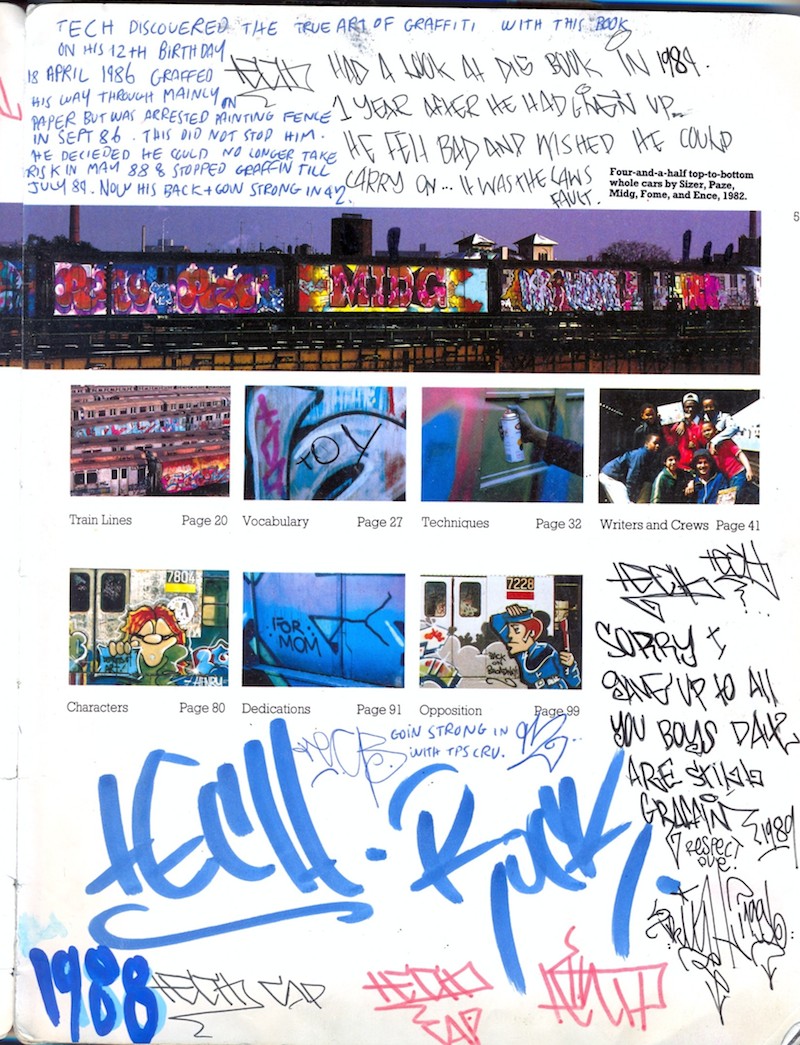

In April 1986 though, a simple book Jessop’s life changed forever. That book was Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant’s Subway Art. One Saturday afternoon, his friends visited the town of Milton Keynes and saw a copy of Subway Art at the W H Smith bookshop there. They were amazed and told Jessop about it, but they didn’t have a copy to show him. So Jessop and friends went back up to Milton Keynes the following Monday and managed to steal one copy of Subway Art. Sitting outside the shop, they flipped through the pages in complete amazement. Before that, Jessop hadn’t even realized that graffiti was meant to be painted on trains. All he had done or seen was graffiti on walls. Unfortunately, they were caught later that day trying to steal in another shop, and so they lost the book. A month later, on Jessop’s 12th birthday, he was given both a copy of Subway Art and the film Beat Street. Jessop still has his original copy of Subway Art.

Scan from James Jessop’s copy of Subway Art, contents page. Courtesy of James Jessop.

Jessop loved what he found in that book, and he would try to copy it. Rather than picking a name, he was still imitating others, but now he would do things like try to copy pieces by Richard Mirando aka Seen from Subway Art. Jessop’s copy was the 2nd printing of Subway Art, but he didn’t know that, and he assumed that he and his friends were pretty much the only people in the country who knew what was up. Subway Art became a sort of bible for Jessop, and today the book is one of the strongest influences on his fine art. Today, he still bases some of his paintings on photos from Subway Art, and is very clearly still obsessed with the book.

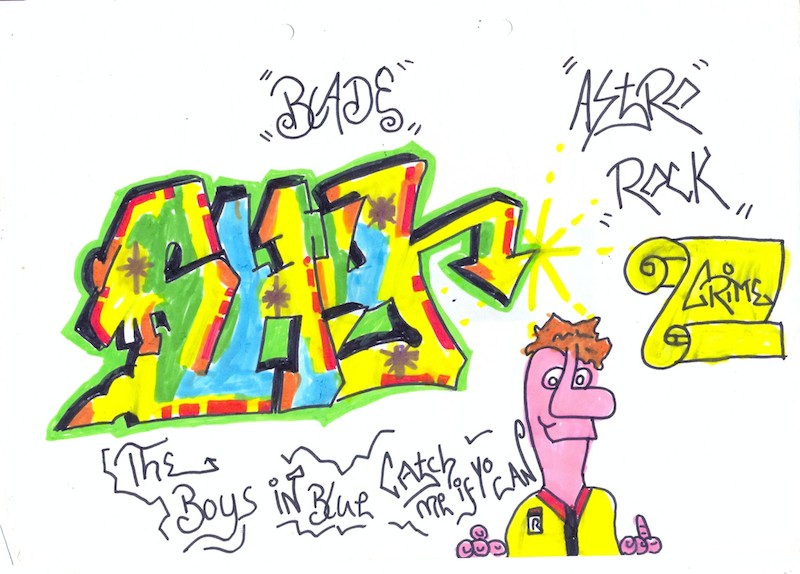

Sketch by James Jessop (1986) copying a SHY piece from Subway Art. Courtesy of James Jessop.

Nearly a year after getting Subway Art, Jessop and some friends took a trip to London because they had heard that there was graffiti there. That was the first time that Jessop saw graffiti in person where the writer was writing his own name rather than a slogan or copying a piece from a book of someone else’s name. The boys also saw graffiti that looked a lot different from what they knew, and thought it to be a uniquely-London style. As it turns out, perhaps some of it was, but the boys were also just seeing the developments that had been made around the world since Subway Art, which was the primary point of reference for what graffiti looked like despite being so outdated. The boys started making regular trips to London, and discovered that there was a London Writers’ Bench in Covent Garden, as well as a piece by the New York writer T-KID. It was at that bench in 1987 that Jessop met the British writer Robbo for the first time. While Jessop was still by his own admission a toy, he and his friends were beginning to get exposed to some real local graffiti by spending time in London, but Jessop was still almost entirely ignorant of what was going on outside of his own town and London.

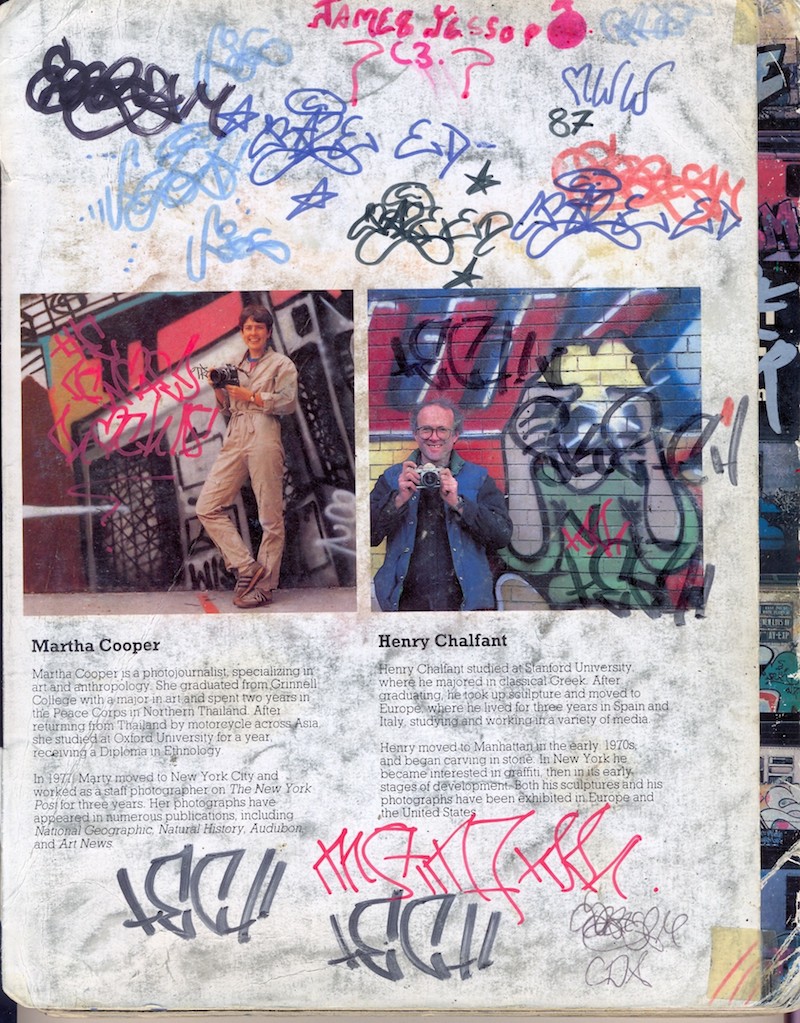

James Jessop’s copy of Subway Art, back cover. Scan courtesy of James Jessop.

It was not until more than a year after seeing Subway Art that another book, Spraycan Art, was published that showed Jessop the significant stylistic developments in graffiti since Subway Art was first published in 1984 (with, of course, images of trains that were painted years before that). Chalfant and James Prigoff’s Spraycan Art profiled graffiti scenes that had sprung up in cities around the world since Subway Art, Beat Street, and Wild Style had inspired kids everywhere to pick up spray cans. Although not the revelation that Subway Art was for Jessop, Spraycan Art was still an key update on the global state of graffiti.

Despite his love of graffiti from a young age, it wasn’t until he was 14 that Jessop painted his first full trackside piece. Just going out and writing any night of the week wasn’t an option for Jessop when he first getting into graffiti. At 12 or 13, he was not not allowed out after dark, which made painting difficult. What complicated things further was that his parents would not allow him to have any spray paint in the house. It was not until he moved out of his parents’ home and went to the Coventry School of Art and Design for university at age 18 that he finally began to write graffiti seriously and, in his own opinion, really became a writer.

At university, Jessop was discouraged from doing graffiti, but he decided soon after he got there that his goal in life was to turn graffiti into an art career, like he had see happen for Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Of course, Haring and Basquiat were not exactly writers, but they both respected graffiti. In 1992, Jessop got a copy of Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography by John Gruen. It was primarily that book that inspired him to keep up graffiti and consider it on par with or even superior to his indoor work. Haring himself praised tagging and graffiti writers like Leonard McGurr aka Futura, whom Jessop respected, contributed to the book. While he was at art school, Jessop says he was really thinking “How can I be an artist and learn, but use what I’m learning during the day to get better at graff?”

Dynamic Liveliness (1998) by James Jessop. A reinterpretation of Peter Paul Rubens‘ Hero and Leandro. Photo by James Jessop.

Around the same time that he got the Haring biography, Jessop finally saw the classic documentary Style Wars for the first time. Despite writing for the better part of a decade by that point and knowing about Style Wars for many of those years, Jessop had never been able to track down a copy of the film. By the time he saw it, the film was interesting to him but also quite dated in terms of the graffiti depicted.

While opportunities to see lots of graffiti at once in books or videos were rare, Jessop did have the occasional magazine or newspaper clipping to update him. Particularly helpful for Jessop was Hip Hop Connection, a magazine founded in the summer of 1988. When Jessop was reading it in the 80’s and early 90’s, the magazine featured a two-page spread on graffiti in every issue. Most of the rest of the magazine was devoted to rap music, but those two pages were enough for Jessop to pick up the magazine whenever he could. That was his only regular source of graffiti photos.

As time went on, Jessop became more entrenched in graffiti culture and better at finding information about graffiti in the United Kingdom and abroad, but his entire career has been shaped by the limited information he was exposed to during his early years as a writer. Jessop’s story is not an uncommon one, particularly among writers who did not live in New York City or a handful of other urban centers. While kids a few years older than Jessop may have had access to a bit more information more quickly, more opportunities to paint, and a better understanding of graffiti culture, the same introductions into graffiti and the basic lack of up-to-date knowledge about what was going on with graffiti in places other than one’s own city were quite standard in the 80’s and early 90’s.