In Eloquent Vandals: A History of Nuart Norway, Steven Harrington and Jaime Rojo of Brooklyn Street Art write “Going from ‘All City’ to ‘All Timezones’ has radically transformed how Street Artists perceive their work and their audience, with the concept of ‘place’ profoundly altered.”[1] Since work can travel the world almost instantly regardless of the location of the physical piece, place no longer means a physical wall but, rather, a url.

Roa, JR and the artists who participated in The Underbelly Project may have made work intended primarily for a digital audience, but those pieces still made sense to a passerby. The work I will highlight next does not do this. It addresses such a restricted digital audience that it would be nearly meaningless to most people who would chance upon it on the street. Before the internet, such street art would be essentially pointless to make, but now it can be distributed online to reach a geographically disperse niche audience.

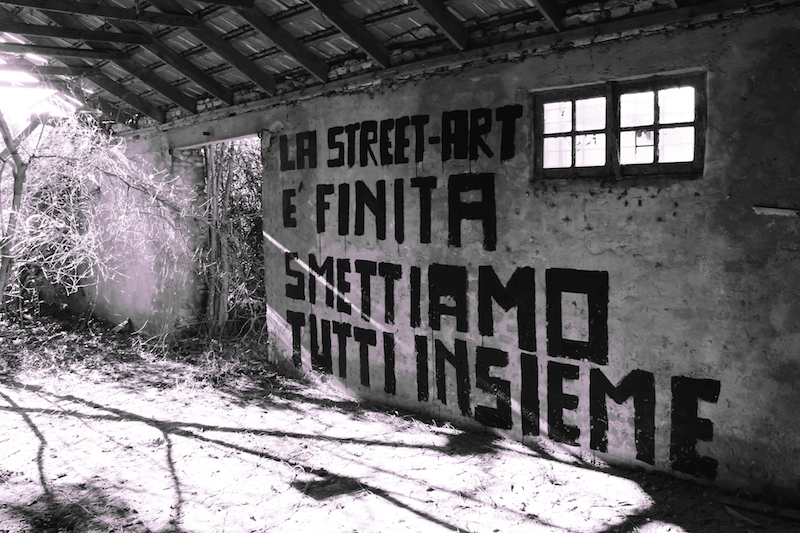

Fine by Elfo. Photo by Elfo.

Elfo’s piece Fine (which references this work by Giuseppe Chiari) appears to be located somewhere in the countryside where few people will ever see it, much like other work in abandoned places. Most work in abandoned places either does not relate to the location, or it does so in some creepy way. With Fine, Elfo was more creative. The work’s text questions the direction street art is headed, saying “Street art is finished, stop all together.” Yet by painting in an abandoned space and then posting a photo of the piece online, Elfo is engaging in the very practices that cause some to say that street art is finished. Who, then, is the work for? Presumably it’s for people who are already street art fans or practitioners. Elfo’s demand is meaningless to a viewer with no connection to street art. While Fine could have been painted in the middle of Rome, the middle of the countryside works just as well, since either site would be equally suitable for taking a photograph to share online.

Sever’s Death of Street Art piece in Hamtramck, Michigan references Shepard Fairey, Os Gêmeos, Barry McGee, Banksy, Futura and KAWS. Photo by Brian Knowles.

One of the most popular examples of street art or graffiti for an internet audience is Sever’s Death of Street Art, painted in Hamtramck, Michigan (outside of Detroit) in the spring of 2012. Most residents of Hamtramck or any other city wouldn’t have recognized all six of the street art and graffiti legends referenced in the piece, but fans on the internet did. Photos of the piece went viral, and it was one of the most talked-about murals of 2012 within the street art and graffiti communities. The piece was clearly not for an audience in Hamtramck, and the fact that it was painted there hardly matters. Like Fine, the mural was for a subset of the Bored at Work Network familiar with street art and graffiti. Its location is “the internet” more than “Hamtramck.”

Elfo and Sever’s pieces address specific but geographically dispersed communities, not the entire Bored at Work Network or the average passerby. In both of these cases, the artists are communicating with people who are familiar with the figureheads and internal politics of street art and graffiti. The same principle would apply had they been targeting fans of a cult television program from the 1960’s or any other niche group with an online presence. Whatever the target audience, the internet becomes a game changer for niche content, and that carries over into street art and graffiti. The people who like Star Trek and graffiti can only be reached online. And it’s not just Elfo and Sever. Many contemporary street artists and graffiti writers are comfortable making work that is completely disconnected from its physical location because they know that they can relocate it within an online community.

- Rojo, Jaime, and Steven Harrington. "Freed from the Wall, Street Art Travels the World." Eloquent Vandals: A History of Nuart Norway. Ed. Victoria Bugge Øye, Marte Danielsen Jølbo, and Martyn Reed. Oslo: Kontur, 2011. N. pag. Print.↵