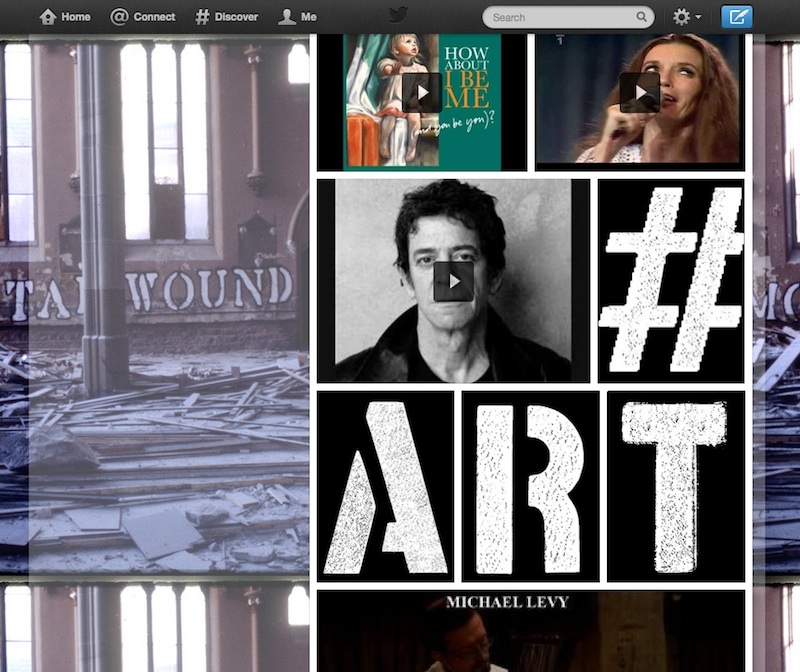

A screenshot from the grid view of John Fekner‘s photo and video uploads to Twitter.

“At its core, street art is the unmediated distribution of art from artist to public.” – Pedro Alonzo

Two of the most interesting opposing strands in contemporary street art and graffiti are the artists who are fully embracing the internet and the artists who are outright rejecting it in favor of “real-world” experiences. Most street artists and graffiti writers fall somewhere in the middle, producing work that looks beautiful on Instagram but doesn’t quite leave walls behind. In the last chapter, I focused on artists in that middle ground who tend toward embracing the internet. In this chapter, I finally highlight the extreme cases: the handful of artists who treat the internet like the street, making art that I classify as viral art. Viral art is where a good chunk of street art and graffiti is heading, or at least should be heading because we’re living online now and an artist’s core reasoning is often very similar whether they decide to make animated GIFs or go out wheatpasting posters.

Pedro Alonzo’s succinct definition of street art, that it’s about artists reaching the eyeballs of the general public without any barriers, is also the most succinct definition of viral art. But there’s a hidden assumption in Alonzo’s definition that by distribution he means putting art on walls. Simply change that assumption from distribution on walls to digital distribution and you get the definition of viral art: At its core, viral art is the unmediated (digital) distribution of art from artist to public.

Intentionally or not, Alonzo’s definition as written implies that the “street” part of “street art” isn’t really about being on a street corner. It’s about unmediated distribution. That’s the root of street art and graffiti. But we in the street art and graffiti communities seem to have lost that.

In order to thrive in this increasingly digital world, we have to let go of paint on walls and wheatpaste and all the other baggage of “street art” and “graffiti.” The first chapter of this book began with a quote from Evan Roth, who suggests that painting on the subway was a hack graffiti writers came up with to distribute their work.[1] Painting on the subway wasn’t the goal. Distribution was the goal. I’ll go further and say that all the techniques we associate with street art and graffiti are hacks. Stencils and spraypaint and wheatpaste and stickers were not originally designed to be used for street art or graffiti. They were taken up by artists and writers and hacked into art-making tools to better accomplish a goal. That’s all well and good, exciting even, except that Ian Strange aka Kid Zoom believes that street artists and graffiti writers sometimes confuse the means of their practice with the ends, and I agree. We’ve gotten hung up on these hacks, this baggage, of street art and graffiti. Those tool are the means and not the ends, and we in the street art and graffiti communities have to stop confusing the means with the ends. We have to get back to that core goal of unmediated distribution and we have to hack new systems to do it.

Whereas once upon a time the street was the best place for unmediated distribution, now that same distribution can happen online in what Roth calls “the public space of the internet.” Still, I doubt I can convince everyone to drastically change their definition of “street art” and discard that “on the street” assumption overnight, and there’s still some usefulness in differentiating between what exists online and what exists on walls, as long as we first acknowledge the similarities. To differentiate between “on the wall” (street art and graffiti) and “on the web” (viral art) distribution, for now I’ll accept Alonzo’s implicit assumption and use the term viral art to describe the digital equivalents of street art and graffiti.

Viral art is street art for those of us who grew up in a post-America Online world. It’s art that bypasses gatekeepers, appeals to the masses and reaches our eyeballs without us having to google “art.” But what it isn’t, necessarily, is “real” in the traditional sense of the word. Viral art does not have to exist now or ever have existed in any form besides a series of ones and zeros (for simplicity’s sake, I’ll generally be contrasting between physical and digital existence in this chapter, although of course those ones and zeros are physical in a sense). In this way, viral art encompasses street art distributed on the internet like we saw in the previous two chapters, but also animated GIF art, Twitter art and more.

Viral art is art for the Bored at Work Network. Roth argues that the Bored at Work Network and the audience for street art are essentially the same and that in both scenarios (discovery on the street or online) the work is being pushed to the audience rather than the audience going out and searching for the artwork, breaking viewers out of their daily routine. Online, photos of street art and GIF animations travel on the same pipelines and appear on the same social media feeds. Differentiating between them at that point seems to serve little purpose. It’s well acknowledged that street art is not an aesthetic style, but a way of distributing art or interacting with space, and viral art is no different. It’s just that viral art uses a slightly different distribution system than traditional street art and graffiti.

When I thought up the term viral art, I did a quick search online in case the term had been used before, and indeed it has been. What I found is kind of funny. There is a poorly written Wikipedia article for viral art that reads like an essay with a novel argument and a critique of past uses of the term rather than an encyclopedia article. The article, mostly written in January of 2008 by a user who went by the handle “The Defective Detective,” actually argues for a similar definition of viral art as what I have laid out here and will continue to expand on throughout this chapter. The Defective Detective cites street art as the start of viral art, and considers street art that has been photographed and shared online as an extension of that. The Defective Detective applauds viral art because “It takes the middleman out of the equation, e.g. the gallery owner, the museum curator, and for this reason it can be as original, activist and satirical as the artist wishes. And because it’s cheap, easy to produce, and distribute, it can be accomplished by anyone with a video camera, computer, and active imagination. It opens up art to the widest audience there is, anyone with an Internet connection.”

There are two kinds of viral art: organic viral art and invasive viral art.

Organic viral art is viral art that is distributed by people choosing to share it, such as an artist posting a photo to their website and having their fans reshare it on various social media networks. Organic viral art can definitely still be interesting and even brilliant, but it doesn’t take full advantage of internet’s potential for unmediated distribution of art from artist to public. Discovering art because it’s been shared by someone you have opted-in to follow is not the same as stumbling across art that has been installed without permission. A person sharing content on their blog or other social media outlet selects what they want to share and what they do not, so they function as micro-gatekeepers and mediate a portion of their followers’ experiences.

Most viral art is organic viral art. Indeed, “viral videos” and the vast majority of “viral media” as we know it would fall into the organic category. It’s basically the traditional idea of how we think of viral content: It spreads along natural streams of interconnected people sharing content, which is why I call it organic.

Occasionally, invasive viral art pops up. Invasive viral art is viral art that most accurately fits the requirement of unmediated distribution. The distribution of invasive viral art doesn’t have to happen along the natural sharing streams that organic viral art travels. Invasive viral art invades space and is inserted where it “doesn’t belong,” but what differentiates it from street art and graffiti is that invasive viral art invades digital space, typically the public space of the internet.

While I will go into more depth throughout this chapter about organic viral art and how digital work like animated GIFs or viral videos can be similar to street art and graffiti, what is most exciting to me is invasive viral art; works that truly takes advantage of the internet. The artists making invasive viral art are using the internet as a street or a place to find people, rather than just a place to store or maybe share things.

- Roth, Evan. "Evan Roth." Interview by Alexander Tarrant. Juxtapoz Oct. 2010: 124-35. Print.↵