Various graffiti zines. Photo by Adam Void.

“Zines were important in the 90’s and early 2000’s because they were the link between picture trading and the internet. Picture trading was these big piles of loose images. Zines collected them into a hard copy bound format where they are all collected together. Later, that manifested as websites.” – Adam Void (aka AVOID pi)

Like many DIY art and culture movements, graffiti has long been documented through the creation of specialized zines. Zines are essentially homemade magazines that practically anyone with access to a printer can make. Graffiti writers have been making zines since at least 1979,[1] with zines focused on graffiti coming to prominence in the 1990’s.[2] These publications were the stepping-stones between flick trading and full-fledged magazines/the internet, but zines have also continued on their own path even after the advent of professionally-produced graffiti magazines and websites.

A simple zine is easy to make. It does not need to take much time or expertise. Rather than lay the pages out in any professional manner, a zine editor can simply cut and paste (in the physical sense) photographs and text onto pieces of blank paper, which then get photocopied. Depending on the length of the zine, the photocopies can then be folded and possibly stapled. In an afternoon, an active writer or a fan with a bit of content can make their own publication and start distributing it among their friends and contacts. Or they can distribute their zine by just leaving it around at coffee shops or music venues alongside other zines. A zine really could be as simply designed as photos taped to a sheet of paper and photocopied. That could still be an effective source of information and fame for writers, but not all zines are so simple.

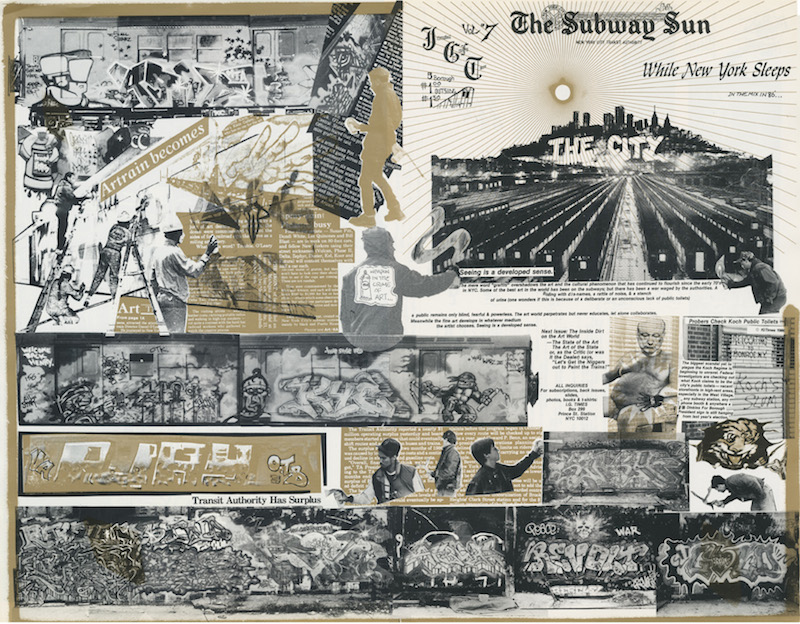

IGTimes volume 7, 1986 – broadsheet (17″x22″) with a quarter fold – designed by founder/ publisher David Schmidlapp, a photographer / filmmaker who did photo collages and photo layouts in the mid-1970’s. Courtesy of David Schmidlapp.

More complex zines can easily be artworks, rather than solely publications for writing documentation. This trend of zine as artwork started happening fairly early on in the history of zines and continues to this day. IGTimes, the first zine about writing on trains, was initially conceived by David Schmidlapp in 1984 as a series of artworks about art and brought on PHASE2 as an art director starting with their 8th issue in 1986. Further developing a design aesthetic also used by Schmidlapp, PHASE2 incorporated complex collages into the zine that would mix together photographs, text and sketches.[3] IGTimes and similarly complex zines still distributed documentation of writing and piecing, but they did so in a way that transformed the original pieces into a part of a larger whole, the zine/artwork.

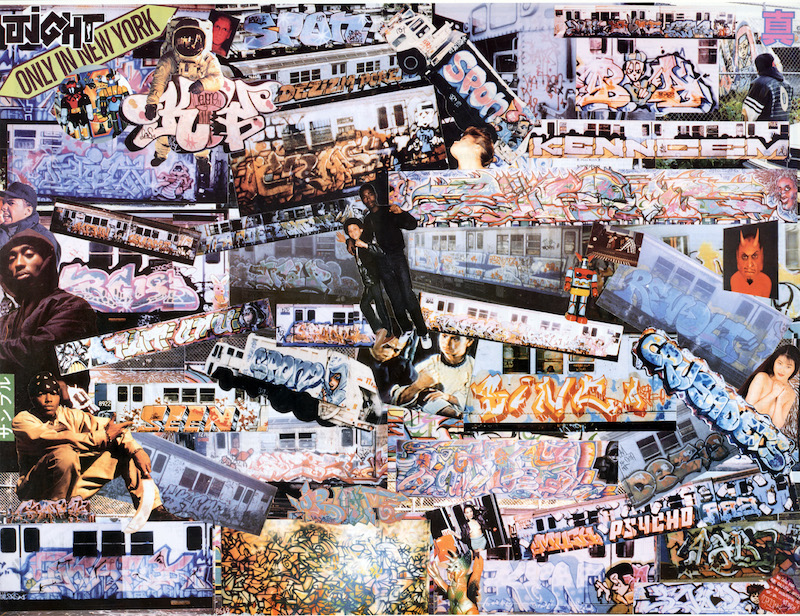

The center page of IGTimes volume 14, 1994 – broadsheet (17″x22″) with a half fold. Design by PHASE2, early 1970’s godfather of aerosol lettering and major flyer designer of early ‘hip hop’ events from the late 1970’s. Courtesy of David Schmidlapp.

Despite the existence of zines as artwork, the primary function of most zines, particularly early on, was to print distribute photographs in a more efficient way than flick trading. While the full-color 8×10 photographs that one might get through flick trading are certainly a higher quality print than can be found in any zine (which are often black and white publications printed as cheaply as possible), photocopying 1,000 copies of a zine full of dozens or hundreds of photographs was more appealing to many writers than the prospect of printing out a tiny fraction of that many photographs for the same cost. This is not to say that flick trading disappeared once zines came into play, but zines did surpass flick trading as a cheap distribution method for photographs (although reproduction quality could suffer).

More design-savvy and business-savvy graffiti writers and fans made magazines, which came into prominence around the same time as the zines. One of better-known graffiti magazines was 12ozProphet, which was started in the early 1990’s by Allen Benedikt aka Raven. Whereas zines were basically made with x-acto knives, glue, paper, and photos, Benedikt had access to a scanner and 12ozProphet was digitally designed. Benedikt wanted to take what the zines were doing and professionalize it; he wanted to make a graffiti magazine.

Caleb Neelon aka Sonik met Benedikt on the streets of Providence, Rhode Island where they lived and began writing and editing starting with the magazine’s 3rd issue in 1996. Neelon got his start with 12ozProphet by writing the introduction for the issue’s cover article, an interview Benedikt had done with graffiti legend Barry McGee.

Some publications started out as zines and developed into magazines, and often the line between magazine and zine was blurry, but magazines have continued to develop into more and more professional publications or die out due to online competition, whereas zines, by their very nature, have retained the DIY ethos and production value. Not anyone can make a magazine, but anyone can print up some zines.

Most graffiti magazines actually started out as zines. By the time Neelon began working on 12ozProphet, it was a magazine as far as the graffiti community was concerned, but that was a matter of perspective. 12ozProphet had worldwide distribution. It had advertisers. It was digitally designed. There were editors. It was in many ways a brilliant publication, but it was also at times amateurish compared to a “real” magazine. Worldwide distribution often meant swapping with other graffiti and hip hop magazines in other countries by sending a few boxes of 12ozProphet issues to them in exchange for receiving a few boxes of their magazine and trying to get the stores in the USA that stocked 12ozProphet to also take a few issues of the foreign magazine. While 12ozProphet had a circulation in the tens of thousands, that was a drop in the bucket compared to professional magazines. The advertisers in issue 6 included Shepard Fairey and a distributor of graffiti magazines, not car companies and department stores.[4] Neelon himself acknowledges that next to a handmade zine at a hardcore show, 12ozProphet looked like a magazine, but next to an issue of Time or Newsweek, 12ozProphet was clearly a zine.

According to Neelon, magazines like 12ozProphet, Skills (edited by Greg Lamarche/SP.One), On The Go (edited by Steve Powers/ESPO), While You Were Sleeping (edited by Roger Gastman) and others were how artists like McGee, Brian Donnelly aka Kaws, Fairey and others received their initial national exposure.

The most famous article in 12ozProphet came about when Neelon and Benedikt visited São Paulo in late 1997 to see a completely different world of graffiti and meet Os Gêmeos, Brazilian identical twin graffiti writers who become the cover artists for 12ozProphet issue #6 in 1998. It was their first time getting press in North America, and it ended up being the article that introduced their work to the world. Subsequently, the twins have been acknowledged as not only some of the most important Brazilian graffiti writers of all time, but among the most important graffiti writers anywhere in the world and two of the most successful fine artists to have roots in graffiti. As the Os Gêmeos article shows, 12ozProphet and other graffiti magazines were essential links between graffiti in different cities and countries around the world in the mid-1990’s.

The power of graffiti magazines is that they had a much wider distribution than the average zine, but they were still made by people within the culture and with a much quicker turnaround than a book. Neelon cites new technologies such as scanners and desktop publishing software that became available in the early 1990’s as essential tools that allowed 12ozProphet to be a more professional publication. So while some people, primarily college students or people with access to university computer labs, could start making magazines around the time 12ozProphet was being published, it was not a path that was open to everyone and zines were still the publishing method most available to the average writer.

- Austin, Joe. "Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City." Google Books.↵

- "Art Crimes: Graffiti Magazines." Art Crimes.↵

- Austin, Joe. Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City. New York: Columbia UP, 2001. Google Books.↵

- Benedikt, Allen, ed. 12ozProphet Issue 6 1996: 1. Web.↵