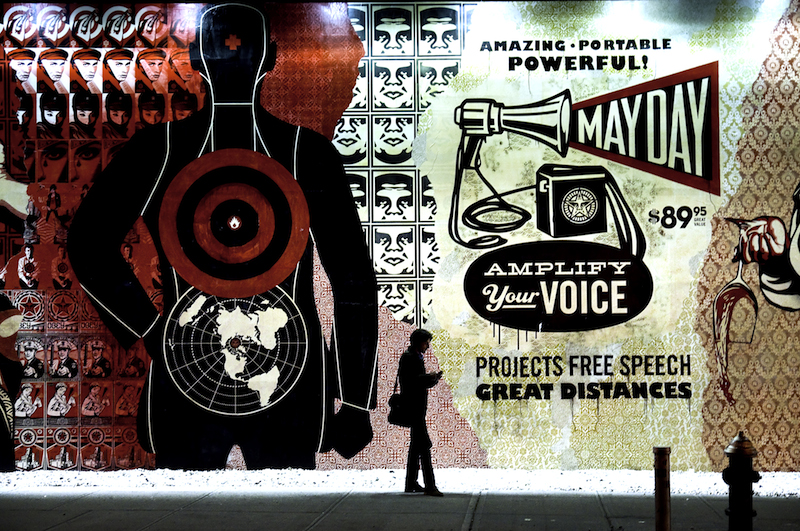

Shepard Fairey’s mural at Bowery and Houston in New York City in May, 2010. Photo by sari dennise.

Shepard Fairey has been consistently putting up street art since before I was born, and he has been one of the most important participants in the street art community as it has grown from graffiti’s nameless oddball cousin to the behemoth that it is today.

As explained in the first chapter, Fairey’s first time showing his OBEY Giant work in a gallery was in 1994, and he had already been making Andre/OBEY stickers for about five years when that happened. But printing stickers and posters wasn’t free, even though Fairey did run a printing studio. In 1995, Fairey set a goal for himself of funding the outdoor portion of the OBEY Giant campaign by selling fine art prints of the same images. He had already been using the same supplies and printing process to print both his street posters and the fine art screenprints. The only difference between the two was that the posters were on cheap paper ideal for wheatpasting and the fine art prints were on high quality paper suitable for hanging on a wall. While he sold some prints, it was not yet enough to entirely offset the cost of the posters he was making for the street. That wouldn’t come for a few years.

Here’s Fairey on some of the problems he faced selling prints in his early years:

“It really wasn’t a very practical strategy until the internet, and here’s why: Packing and shipping prints is time consuming. There’s a lot of damage when you’re sending them off to retailers who often wanted them on consignment. Stuff would sit around, no one would buy it, and it would come back to me damaged. Or I would run ads in places like Slap or Juxtapoz. It’s expensive to do that and that ad is only in there for one issue. I would barely get enough orders to pay for it. I started my website in ’97, and really only because a friend of mine said he would program it for me. I thought ‘well, this kind of street art culture is all about rebellious people who think that life should be a dangerous visceral pursuit, and the internet is about being complacent and voyeuristic and it’s the opposite. None of these people are gonna wanna look for my stuff on a computer. That’s nerdy.’ But, with the opportunity to have a website without having to pay for it, I thought ‘Why not?’. Immediately, within a week of the site being up, it was getting a decent amount of traffic. I set up a shopping cart there and I started to get online orders, but I didn’t have PayPal, so people would still have to send a check in, which is crazy. But in 1998, Juxtapoz did an article on me and they had a big following, and then I got PayPal around then, and that made a huge difference. In a lot of ways, the same problem exists with galleries, with clothing retail, and with poster retail: That there’s an intermediary that you have to deal with, and no matter how professional you are, they might screw things up. Once I had PayPal set up and that Juxtapoz article, all of a sudden, I was controlling all of the steps in the process. That made a huge difference. It was virtually life-changing.”

Four prints by Shepard Fairey. Original photo by Urbanartcore.eu, edited by RJ Rushmore.

Fairey isn’t the only artist for whom the internet and ecommerce made a huge difference. Patrick Miller and Patrick McNeil of Faile say that their webshop, where they sell prints, allowed them to become full-time artists. While I cover a lot of “commercial street art” in this book, the commercial aspects of street art are not my focus. It is, however, a topic that writer and curator Pedro Alonzo has thought extensively about and it deserves a brief mention. Alonzo notes that prints were once an afterthought for artists, images based on paintings that were their primary and more reliable income. But prints have become huge business in the last decade, particularly in the street art community, thanks to webstores. Online, artists can sell out a print release in a matter of minutes and make hundreds of thousands of dollars in one day, a business model that Alonzo sees as a modern version of what Keith Haring was trying to achieve in the 1980’s.

Although the internet has been a huge help to Fairey, he seems to miss parts of the culture that the internet has left behind or changed. He says:

“Street artists and graffiti artists were building a reputation almost completely on personal confrontation with the art and the volume of what they had on the street. You’re walking around New York and you see Revs here. Cost there. So-and-so there. And you go ‘Wow. That person’s putting in work. That is really impressive. They get my respect. They’re all-city.’ You don’t even hear the phrase ‘all-city’ anymore, really. That used to be the big thing. Then, there were some graffiti magazines, and people would get a little bit of love and a second ripple effect of the work they were doing on the street by documentation in the graffiti magazines, but the primary mentality of the street artists and the graffiti artists was to do a shitload of stuff. Things like the throw-up evolved out of the idea of trying to balance quantity and quality in graffiti, that you come up with a thing that’s just two colors, is quick to do, that looks well-resolved stylistically and covers some surface area, and it’s not nearly as much time as a 20-color burner. And with street art… the poster: put up a lot of the same poster; stencils and stickers: put up a lot of the same thing, and it’s what you can carry around in a messenger bag or a backpack. And doing a lot was important because some people might not venture from city to city or neighborhood to neighborhood, so you had to cover a lot. Then the internet, in a lot of ways, changed the approach for people who knew that they could do a few really well-crafted pieces outdoors and get the cachet of doing street art and being in public, but spend a little bit more time and document it well and then have it proliferate like mad on the internet. I’m not saying one is better than the other. It’s just that if you expected to build a name in street art before the internet, you couldn’t have used that approach.”