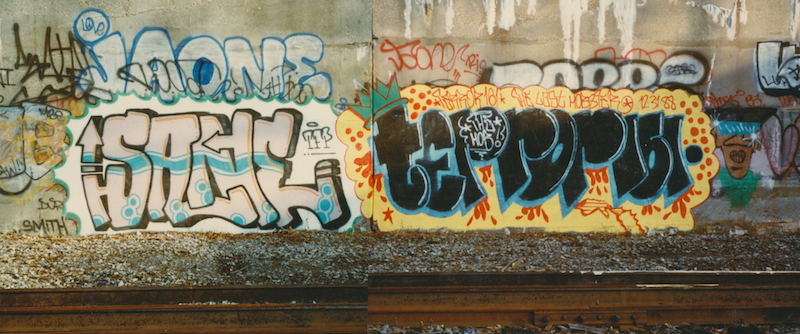

Sane and Terror161 in New York City in 1988. Photos by Sane, courtesy of Jay “J.SON” Edlin, stitched by RJ Rushmore.

Imagine being 13 years old, taking the bus to school every day, and seeing graffiti cover the walls of Harlem and the South Bronx on your way to Manhattan. You start to think about names. Who were these people? How could they be everywhere and anonymous simultaneously? Eventually, you decide to begin writing on the back seat of the bus, a safe place, where nobody would ever see your moniker, then the streets of your isolated Bronx neighborhood. First write with toy markers, then spray paint. As you struggle to rise to the top of the fame charts, one day you hit the inside of a subway car. And then you do it the next day. And it’s a thrill. You may not know anyone else who writes graffiti, but now you’re a writer. After that, only the yard missions fueled by visions of your own masterpieces running alongside the greats like MOSES 147 and Cliff 159 will suffice.

That’s how a lot of graffiti writers started out. That, or they had one or two friends who wrote and introduced them to the scene. But there was no instruction manual or online course that could give any real hint as to what graffiti was or how to get involved with it. If you only rode specific lines, you knew the kings of those lines, but you probably had little clue what sort of work was going up elsewhere in town, and seeing graffiti certainly didn’t mean that you knew how it was made.

Jay “J.SON” Edlin, aka TERROR161, J.SON, and other names, began writing in 1973. That means that he began before much of the media attention that would put graffiti on the map: before Subway Art, before Style Wars, before Wild Style, before articles in The Village Voice, before the Beyond Words show, before Henry Chalfant showed at OK Harris and even before Norman Mailer’s Esquire Magazine article “The Faith of Graffiti” (or the subsequent book by Mailer, Jon Naar and Mervyn Kurlansky). Compared to the rest of the city, Edlin was living in an area with very little graffiti, but he saw it when commuted through the South Bronx and Harlem to school in Manhattan. Mostly, he took the 1 line, which was the first line where graffiti appeared on the outside of trains. Edlin started out writing in his own neighborhood, with no clue about seemingly basic things like how to get into train yards or how to acquire the markers such as uni and min-wides used by the more established writers he sought to emulate.

In what Edlin describes as “a lucky break,” he found out that a friend of a friend was also a writer, and that friend knew the location of a shop where graffiti writers were getting their supplies like markers for tagging the insides of trains. Thanks to that tip, he went to the shop and hit pay dirt: Uni’s , mini’s pilots and a rainbow coalition of flo-master inks. Edlin was ecstatic, but his elation was short-lived. After buying several of the elusive markers he had sought, he was accosted and robbed by MOSES 147, King of Broadway, upon exiting the store. Shark ate minnow. For Edlin, that early era was the golden age of graffiti, a time when he only knew a couple of toys (amateurs) from his neighborhood but saw and became familiar with the names of kings just by seeing their work run.

Communication amongst writers, particularly those who did not want to risk getting mugged or beaten up, was extremely limited. Spots like The Writers’ Bench could be dangerous for anyone who planned to just show up one day without already knowing a regular or two in that crowd. One way that some writers did try to make connections was by writing “X wants to meet Y” at spots where they assumed their target would pass by, but while writing on walls can be great for spreading your name around, it’s obviously not a reliable way to plan meetings.

Chance encounters helped too, and tended to be less dangerous than going to The Writers’ Bench. If one writer saw another one catch a tag, they might introduce themselves, but there were less obvious signs too. Like most writers, Edlin liked to watch the trains go by. If he saw another teenage guy watching the trains go by, Edlin figured there was a good chance that the other guy was a writer too. Edlin also noticed that many writers dressed the same or had paint and ink stains on their hands and clothes. Again, there was a good chance that a teenager with ink-covered hands was a writer, and so if one writer spotted another’s stained hands or clothing, they might say “Yo, you write?”

Edlin recalls one way, perhaps the most ironic way, of meeting other writers; it is something that only happened to him once and he describes it as “the greatest graffiti experience of my life.” He had been arrested in 1975, and was sentenced to go to a subway station and clean graffiti off the station with other writers. By getting all of these writers together to clean up graffiti, the NYC judicial system inadvertently connected groups of writers from disparate parts of the city. Without getting apprehended, these writers would have only known each other by reputation – networking at its finest. This makeshift buff-squad turned out to be a great way of connecting writers from various parts of town, allowing them to trade info on yards, paint racks and lay-ups out of their normal jurisdictions. Edlin even remembers kids who had not been arrested showing up “just to hang out and meet people.”

Eventually, Edlin would go to the Nation of Graffiti Artists meetings, which was an arts program and studio space specifically for graffiti writers. It was founded in 1974 to move graffiti writers from illegal painting towards legal work and potentially even careers in the arts.[1] Initially writers went there and created canvases and experienced writers mentored novices. Eventually however, much like the court-mandated buff squad, rather than get writers off of the street, it ended up being a place for artists to meet people from other parts of the city, stash paint and conspire to bomb trains.

After a few years on hiatus, Edlin picked up graffiti again in 1980, but things were quite different from how he remembered them. This was shortly before writers and the poseurs that followed started showing in galleries, and those shows were a new way for writers to meet one another. Everyone could show up to openings, see some art and meet other writers who were all fans of the same artist or artists in the show (or, potentially, had beef with them). A stable community was beginning to form, but graffiti had became about the money rather than the fun and the rush of it, and it just wasn’t as interesting to Edlin, who continued to show on transit only.

- Austin, Joe. Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City. New York: Columbia UP, 2001.↵

Pingback: A New Era – How the Internet Changed Art | Digital Media Culture

Pingback: A New Era – How the Internet Changed Art – Final | Digital Media Culture