A series of security gates painted by Stephen “ESPO” Powers. Photo by Jake Dobkin.

In The Adventures of Darius & Downey: & Other True Tales of Street Art as Told to Ed Zipco, there’s a story told about the time when Leon Reid IV (Darius) is hanging out in Cincinnati with his friend Merz and being shown photographs of graffiti, including some work by Stephen Powers aka ESPO. There was a photo of one Powers’ famous gates, but Reid had never seen anything from the series before, nor had they heard about the series. Merz told Reid to “think big,” as Reid examined the photo and tried to figure out what the hell he was meant to be looking at. Finally, it clicked: Powers had painted his name on the security gates in a subtle way that didn’t look at all like graffiti. If you didn’t know what you were looking for, you probably wouldn’t see anything. And when you figured out what was going on, your mind was blown. With the gates, it really took a photograph for things to become clear. Flick trading and word of mouth ended up working out fine for Powers in this case, but I can’t even imagine how popular those images would have been had the internet been more widely used when he developed that style.

An ad takeover by Jordan Seiler from his Weave It! series, which he describes as “an ongoing collaboration between PublicAdCampaign, National Promotions of America and its sister company Contest Promotions.” Photo by Jordan Seiler.

Jordan Seiler has done some pieces that seem to me to relate to Powers’ gates. I mention Seiler’s Weave It! series in this section because, like some op art, the series involved simple geometric patterns, but also because the pieces created a sort of illusion in public space that public advertising did not exist there. If you were looking for it and happened to pass by one, you might have noticed one of Seiler’s Weave It! ad takeovers. But if you weren’t paying attention, the pieces were easy to miss, blending right into the background of the city. These were not as eye-catching as big black and red wheatpastes by Shepard Fairey. Maybe one of Seiler’s takeovers would catch your attention for whatever reason and you would realize that the simple construction-paper pieces must have been the act of an activist rather than the billboard company, but I’m doubtful that many people had that experience in person.

I think most people who passed by a Weave It! takeover just got to go on with their lives with less advertising bombarding them and didn’t have to think much of it. And that’s okay. Seiler was able to remove advertisements without turning his anti-ads into advertisements for his own work. Instead, he documented the takeover with photographs and posted those photos online, calling attention to his actions in a way that lasts longer and reaches more people than a poorly documented ad takeover saying “FUCK BILLBOARDS” can do.

“Untitled” by Know Hope. Photo by Know Hope.

Know Hope’s outdoor installations are like subtle performances, but even as the work changes over time (both due to the artist’s hand and otherwise), viewers may not realize that the changes are part of the art, or that the piece is an artwork at all. Know Hope is perhaps best known for his paintings and wheatpastes, but he has also done a number of sculptural installations outdoors that are designed to change over time. These installations often involve a combination of a sculptural element and text written on a nearby wall. The installations can be super-ephemeral or at least change over time because the sculptural elements are particularly temporary and subject to being removed. For the piece shown above Know Hope wrote text on a wall and then went back after three days to modify the work slightly by placing a flag sculpture on the ground near the text. This was done with the hope of “fabricating a coincidence” or slightly strange situation for a viewer who would be unlikely to identify the work as an art installation but might have seen the site before Know Hope installed the piece, after the initial installation, and after he modified it. Whereas a mural signals “I am here on this wall and I am a complete artwork contained within these boundaries,” Know Hope’s goal with these types of pieces is to require the viewer to actively participate and identify the installation for themselves by connecting the various components of the piece that may be distributed throughout a space. Know Hope claims that the work is really for the person seeing it in the flesh though, saying, “Because of the ephemeral nature of everything, I make sure to get a photo, but I think I would still be doing the same work even if I couldn’t share the photos online.” I don’t doubt Know Hope, and as viewers online, we only get the finished photograph as documentation of the installation, but that photograph can still spread around the internet and reach a lot more people who will identify what Know Hope is doing as art and that counts for something. Without the photographs, Know Hope might just be some anonymous and unnoticed guy in Tel Aviv arranging stuff on the street in an effort surprise a handful of people. That’s an interesting idea in theory, but doing the exact same thing and documenting it opens of the possibility of a successful art career rather than complete obscurity.

Admittedly, these are not examples of truly invisible artwork. The pieces still identifiable as art by those particular artists if you know what you’re looking for, which is kind of the point, particularly for Powers’ gates. Some street artists have taken things beyond that though, to interventions that are effectively invisible once completed.

I should note that by “invisible” I mean to say that these are artistic interventions that could not be identified as such without assistance and therefore effective invisible, although still not necessarily actually invisible. This kind of work is almost entirely a subset of conceptual street art.

My favorite example of effectively invisible street art is Brad Downey’s work dismantling fake CCTV cameras. Because there’s a video of the piece, anyone who views it can more or less figure out what’s happened: Downey learned that many property owners just buy the casings for CCTV security cameras as a crime deterrent rather than buying and maintaining actual cameras and he also learned what the fake cameras tend to look like, so he decided to uninstall some of the fake cameras that he found around London. However, if you’ve never seen the video and you’re just walking around London, you would never know what Downey did, and although it could be argued that the piece was a performance, he wasn’t performing for a live audience but rather the audience that would see the resulting video. Someone who encounter’s the results of Downey’s intervention might feel more or less comfortable walking past a building when you notice that it seems to be the only one around with no CCTV cameras, but they couldn’t possibly attribute that to Downey’s actions. Since it’s an intervention on the street and it’s art, I think it’s fair to call the work street art, but it’s also effectively invisible in the traditional ways that we would consider street art visible. Downey’s work begs the question; does an intervention have to be noticeable as one for it to be a true intervention? I say no. Even if nobody notes Downey’s work as an intervention, he’s still changed the city. It’s a bit like asking if it’s worth picking up a piece of litter off the ground if there’s nobody around to see you do it.

Lee Walton’s video Making Changes is similar and almost as awesome. Walton is not generally classified as a street artist, but he does make artworks in public spaces, some of which are done without any permission. In Making Changes, which takes place outdoors throughout New York City, Walton is shown repeatedly walking into the frame of a shot, moving around one or two objects that he finds himself in front of to a different place or into a different position and walking out of frame. This pattern repeats itself in different locations for nearly four minutes. The people I’ve shown this video to tend to fall into two camps: They either think it is ridiculously stupid and probably not art, or it’s amazing. Personally, I like the piece so much because I dance between those two camps, and that’s interesting to me. Walton isn’t doing anything so rebellious or activist as protesting CCTV cameras, but he is intervening in very small ways in public space. And although his interventions may seem meaningless (what does it matter if Walton swaps the locations of a blue and a green trash can placed right next to one another?), at least one of Walton’s changes had an almost immediate effect that gets captured on the video. This is the change where Walton closes the glass door at the entrance of the “City Barn Antiques” store, a door that appears to have been kept open by a hook attaching the handle of the door to the wall. As the door closes, a couple walks up to it, looks inside of the shop. The shot ends before we see if the couple enters or not, but I think it’s safe to say that their decision could have been different if the door had already been open. Maybe Walton’s seemingly simple change resulted in a sale, or a loss of a sale, for City Barn Antiques. Like Downey with his CCTV Takedown intervention, most of Walton’s changes would hardly be noticed and certainly none would be recognized as the result of conscious art making after he has left the area, but documentation of the performances illuminates the practically invisible physical interventions.

Maybe many street artists have been doing work like this for a long time. Downey and Walton certainly were not the first that we know of to make this kind of street art. Don Leicht was doing practically invisible street art, abstract mark-making to be more specific, in the late 1970’s in New York City, but of course almost nobody saw it and now very few people know that it happened. Similarly, Dan Witz describes creating “shrinelike displays” like Pocket Realms outdoors around the same time out of random bits and bobs that he would find on the street and carry around in his pocket.

“Pocket Realms” (re-created 2010) by Dan Witz. Photo by Dan Witz.

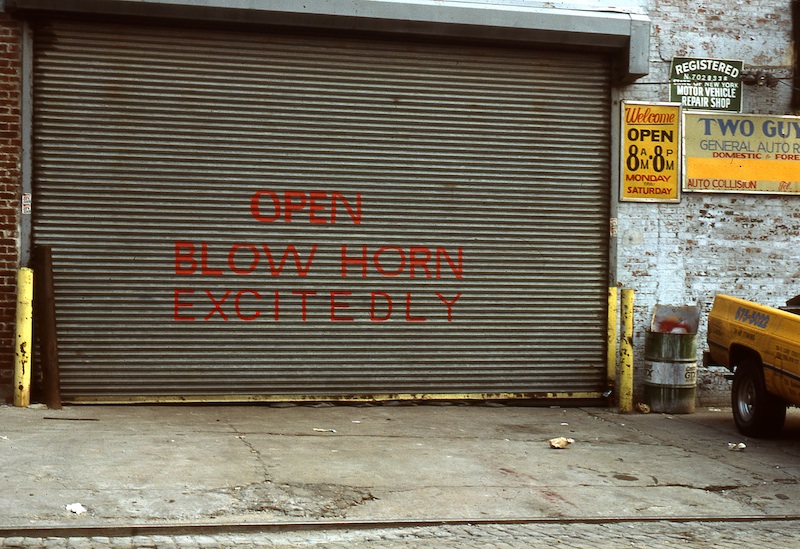

Similarly, one Witz’ famous pranks was so subtle that I doubt many people, even those who saw it and laughed, recognized it as an illegal intervention and not just something the property owner had done themselves: Witz painted the the word “EXCITEDLY” beneath a sign on a garage door that said “OPEN BLOWN HORN” in precisely the right font and color for the word to blend in to the rest of the sign. Luckily, a photo of that piece does exist. While these interventions are addition to space rather than subtractions like in CCTV Takedown or neither additions or subtractions like in Making Changes, Witz’ interventions are still invisible because they are difficult for most people to identify as artistic interventions without the context that documentation provides.

In 1984, Dan Witz added the word “EXCITEDLY” to this sign in New York City. Photo by Dan Witz.

I hate to be the asshole to say that artwork only matters if people see it, but, for better or worse, we live in an age of “pics or it didn’t happen,” but it would be a difficult argument to make that the undocumented invisible works are more than a very interesting footnote in the history of street art while the highly visible and well-documented street art and graffiti made around the same time have had an enormous affect on contemporary and future work.

It’s only in the last few years that artists have been able to make invisible street art that does not disappear completely into the ether. Of course, the things that have facilitated this new age of possibility are cheap cameras and the internet. Before the internet, I imagine that countless artists, some associated with street art and many not, created invisible street art. I suppose that a land artist like Richard Long could fall into this category, but if that work was documented and presented somewhere, it was presented to a stuffy art world outside the orbit of street art or the general public. Before the internet, even if invisible street art was documented, there was really no way for it to reach the general public, only the art world. Now, anyone can make invisible street art and share it with the world.