A wheatpaste of the Lepos character by Diego Bergia. Photo by Garrison Gunter.

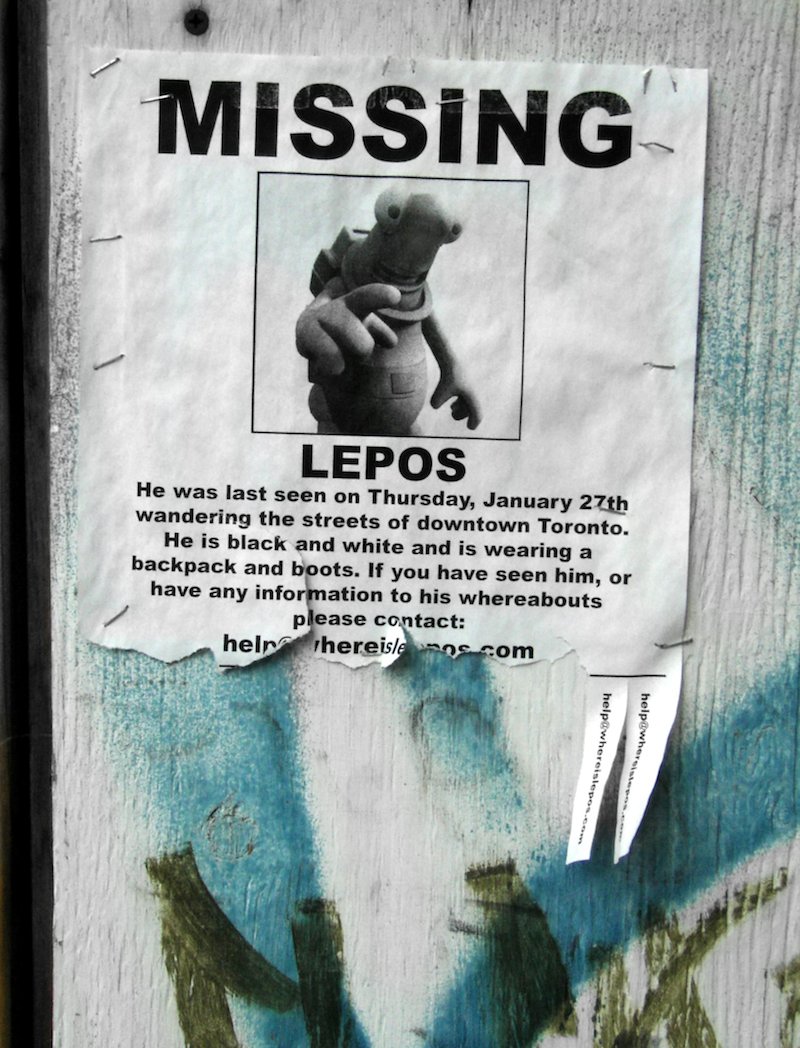

The entirety of Diego Bergia’s Lepos: The Primary Invasion project has to be applauded as a fantastic combination of traditional street art and graffiti with digital art. Bergia began writing graffiti in 1993. He stopped in 2003, but learned 3d animation around the same time. In 2004 he began wheatpasting his Lepos character, something he had originally began painting in the late 90’s to go alongside his graffiti. With the wheatpastes, Lepos took on a life of its own as a street art project. There were wheatpastes around Toronto and other cities, as well as black and white flyers advertising that Lepos was missing and an email address that people could tear off if they wanted to tell Bergia that they had spotted the creature. Bergia also made a video that combined live action and 3d animation, ostensibly showing a “sighting” of Lepos. Eventually, Bergia moved into making short videos that looked like teasers for game on the Neo Geo game system of the early 90’s. The game, Lepos: The Primary Invasion, shows how Lepos is an alien sent to Earth to warn us of an impending invasion that destroyed his planet. In addition to fighting off the invading hordes on Earth, Lepos tries to raise awareness of the invasion by writing graffiti about it. The videos are portrayed as being segments of a real video game, but they’re really just animations, viral videos giving fans of Lepos the character’s backstory. There is no game in production (yet). The whole thing is a fascinating combination of viral art and street art.

What really completes the project and sets Bergia apart is that he’s put Lepos into real video games in the form of in-game graffiti. Lepos can found in the 2006 game Tony Hawk’s Project 8 by Activision, as well as the 2009 game Skate 2 by Electronic Arts. Both skateboarding games (from competing companies) needed some graffiti pieces to decorate their environments. Bergia had friends at each company who asked him if he would like to contribute, so he sent over some graphics and his work wound up in the games.

A screenshot of Bergia’s artwork in Tony Hawk’s Project 8. Game published by Activision and screenshot by Diego Bergia.

For Bergia, getting his work in games was an obvious choice once the opportunity presented itself, saying, “With the Tony Hawk games, you started seeing graffiti in video games, and as a graffiti writer, you just want to get up. And if you play video games, obviously you want your graffiti in those video games. It’s just getting up, basically.”

Bergia didn’t have to break the law to get up with this project, and he was still able to get up and get his graffiti seen in a massive way. More people probably regularly saw his graffiti in-game than ever saw it regularly in person. Skate 2 and Tony Hawk’s Project 8 sold over 4 million units combined globally. That’s a lot of people spending a lot of hours in environments that are covered in Lepos characters and other graffiti by Bergia. By getting his graffiti into these video games, Bergia created an absolutely massive digital viral art component to the Lepos project. What better way to get up on the streets of the digital world by actually getting up on digital walls in a 3d animated environment?

Admittedly, putting your art in a video game with permission of the designers isn’t exactly the unmediated distribution that is ideally part of invasive viral art. Perhaps this these games are really a massive-scale example of organic viral art, but once Bergia’s work was in the games, players still got that same sense of discovery of his work that can occur outdoors or with a piece of invasive viral art on the internet. Unlike Tumblr, where users visit the site with the expectation of seeing art, or Marc Ecko’s graffiti video game, people weren’t expecting to see Bergia’s graffiti when they played Tony Hawk’s Project 8 or buying the game for that reason, an important distinction I think. With the games taken into account, Lepos has been found on the street as a wheatpaste and a flyer, as a spraypainted character as part of a graffiti piece, in animations for a fake video game where people have at least some idea of what they are getting and throughout two mainstream video games as an unexpected background element. And hopefully one day there will be a real Lepos video game. For me, the Lepos: The Primary Invasion project is a prime example of the amazing potential for contemporary art to be found and distributed as street art, graffiti, invasive viral art and organic viral art across a wide variety of environments.

A flyer by Diego Bergia. Photo by striatic.